This time, in the series of incunabula of the month, we will introduce a work by the most influential Christian scholar of late antiquity, a saint of the Catholic and Orthodox Church, Doctor of the Church Aurelius Augustine, resp. Augustine of Hippo (November 13, 354 Thagaste, Numidia (today Souk Ahras, Algeria) – August 28, 430 Hippo Regius). So far, Estonian readers are familiar with Augustine’s famous autobiography ‘Confessions’ (Confessiones, est 1993, 2nd print 2007, trans. Ilmar Vene), which holds a special place in the history of autobiographical literature. Here, we will introduce a work that is considered Augustine’s main work. This is ‘On the City of God’ (De citivitate Dei, written in 413–426).

Augustine was from North Africa. His father was a wealthy pagan Patricius, probably a descendant of a Roman veteran who had landed in Africa and a member of the Thagaste city council, who was baptized in his later years. This was at the instigation of Augustine’s Christian mother Monica. Although Augustine received a Christian upbringing from his mother, it took a long time for him to join the Christian congregation. The young man was attracted by rhetorical studies, the atmosphere of which, shaped by free-spirited fellow students and the metropolitan atmosphere, in Carthage, took him away from his Christian world of origin. He also had a very passionate and sensual character, which led him rather to worldly paths and love adventures. At the same time, Augustine was also passionately intellectual and sought answers to his existential questions. After detours into Manichaeism, academic skepticism, Platonism and Neoplatonism, he eventually returned to Christianity on his intellectual journey. Neoplatonism led him away from Manichaean materialism and towards the recognition of the idea of immaterial reality, after which Christianity seemed reasonable to him. Since one of his role models, the Neoplatonist Victorinus, had converted to Christianity, he felt a desire to do the same. The intellectual conversion was followed by an internal moral struggle, which found its resolution in a famous scene in the garden of his house in the summer of 386: on the other side of the wall a child repeatedly shouted ‘Tolle lege! Tolle lege!’ (‘Take, read!’), whereupon Augustine, taking this as a message for himself, opened the New Testament and read: ‘Let us behave decently, as in the daytime, not in carousing and drunkenness, not in sexual immorality and debauchery, not in dissension and jealousy. Rather, clothe yourselves with the Lord Jesus Christ, and do not think about how to gratify the desires of the flesh.’ (Romans 13:13–14). (‘Confessions’, 8, 8–12)

After his conversion, Augustine gave up the position of professor of rhetoric in Mediolanum (now Milan), which he had obtained after unsuccessful defenses to be confirmed as a rhetoric teacher in Rome. On Good Saturday 387, Bishop Ambrose of Milan baptized Augustine. In the autumn of 388, he returned to Africa, where he founded a small monastery, first in his hometown of Thagaste. In 391, the Bishop of Hippo ordained him a priest, and in 395 or 396 he became auxiliary bishop of Hippo, after which he founded a new monastery. After the death of Bishop Valerius, he became the new Bishop of Hippo in 396. Already at the time of his conversion to Christianity, he had published a number of writings in defense of Christianity, and now his writings gained even greater momentum. Augustine died in August 430, while the Vandals who had invaded Africa were besieging Hippo. (For more information on the life and works of Augustine, see HERE)

Augustine began writing ‘On the City of God’ in 413 against the backdrop of the barbarian invasion. The Visigoths, led by Alaric, had sacked Rome in 410, which was no longer the capital of the Western Roman Empire (the Western Roman Emperor Honorius had moved it to Mediolanum, and after the attack on Mediolanum to Ravenna, which was considered more defensible). As the former capital of the entire empire, considered the ‘eternal city’, Rome nevertheless had extraordinary importance. It was home to an estimated 800,000 inhabitants, making it the largest city in the world at the time. Alaric laid siege to the city as early as 408, causing panic, which led to the consideration of restoring pagan rites in the still multi-religious city. Pope Innocent I is said to have even agreed to this as a temporary solution, provided that the rituals were performed privately. However, when the pagan priests insisted that the sacrifices should still be performed publicly in the Forum Romanum, the idea was abandoned, also due to lack of public interest. As a result of the siege, famine and disease spread, the Roman senators finally turned to Alaric to inquire under what conditions he would be willing to lift the siege of the city. The ransom demanded was so high that corruption arose among the Roman senators, and to make up the missing part, pagan statues had to be melted down, which seemed to contemporaries to be the last vestiges of Rome’s ancient glory and dignity. Honorius agreed to hand over the ransom, and Alaric initially retreated. In 409, however, he besieged the city again because Honorius had refused to pay him the annual tribute. To avoid another famine, the people of Rome agreed to appoint Attalus, a pagan who had refused to be baptized, as a rival emperor to Honorius. In the summer of 410, Alaric, however, stripped Attalus of the imperial office and resumed negotiations with Honorius. However, nothing came of the negotiations, as Alaric was attacked by a supporter of Honorius and returned to besiege Rome. On 24 August 410, the Visigoths entered Rome and plundered it for three days. Several important public buildings were damaged, the tombs of previous Roman emperors were desecrated, and looting, killing and raping took place. Miraculously, the most important churches in Rome, the basilicas of St. Peter and St. Paul, remained untouched by the plunderers, but many smaller churches were still plundered. The Romans were in great distress, and many fled, including to the fertile and prosperous province of Africa, which was located in what is now North Africa. (See more at Sack of Rome (410)) Here, Augustine also encountered the refugees and saw their misery.

After the plundering of Rome, people sought explanations and somebody to blame for the horrors that had taken place. Many Romans saw the event as punishment for abandoning traditional Roman religion in favor of Christianity. It was in response to these accusations that Augustine wrote his ‘Republic of God’. According to him, Christianity was not responsible for the siege of Rome, but rather protected it. Although the earthly power of the empire had disappeared, the Kingdom of God would ultimately triumph, he was convinced. Despite Christianity being the official religion of the empire, its message was, in Augustine’s view, more spiritual than political. In his opinion, Christians should be concerned with the mystical, heavenly kingdom, the New Jerusalem, not with earthly politics. In the book, Augustine presents the history of humanity as a conflict between the Devil and God, between the earthly and the Kingdom of God, which is destined to be won by the Kingdom of God. In his view, the Kingdom of God is represented by people who renounce worldly goods in order to devote themselves to the eternal truths of God, which were now fully revealed in the Christian faith, while the Kingdom of the Earth is represented by those who are completely absorbed in the worries and pleasures of the present, in the passing world. (See more)

‘Thus in this world, in these evil days, not only from the time of the bodily presence of Christ and His apostles, but even from that of Abel, whom first his wicked brother slew because he was righteous, and thenceforth even to the end of this world, the Church has gone forward on pilgrimage amid the persecutions of the world and the consolations of God.’ De civitate Dei, Volume II, Book XVIII, 51 (trans. Rev. Marcus Dods, M.A., see Project Gutenberg)

A state that is not based on justice is no different in his eyes from a band of robbers:

‘Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? The band itself is made up of men; it is ruled by the authority of a prince, it is knit together by the pact of the confederacy; the booty is divided by the law agreed on. If, by the admittance of abandoned men, this evil increases to such a degree that it holds places, fixes abodes, takes possession of cities, and subdues peoples, it assumes the more plainly the name of a kingdom, because the reality is now manifestly conferred on it, not by the removal of covetousness, but by the addition of impunity.

Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, “What thou meanest by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, whilst thou who dost it with a great fleet art styled emperor.”’ De civitate Dei, Volume I, Book IV, 4 (trans. Rev. Marcus Dods, M.A., see Project Gutenberg)

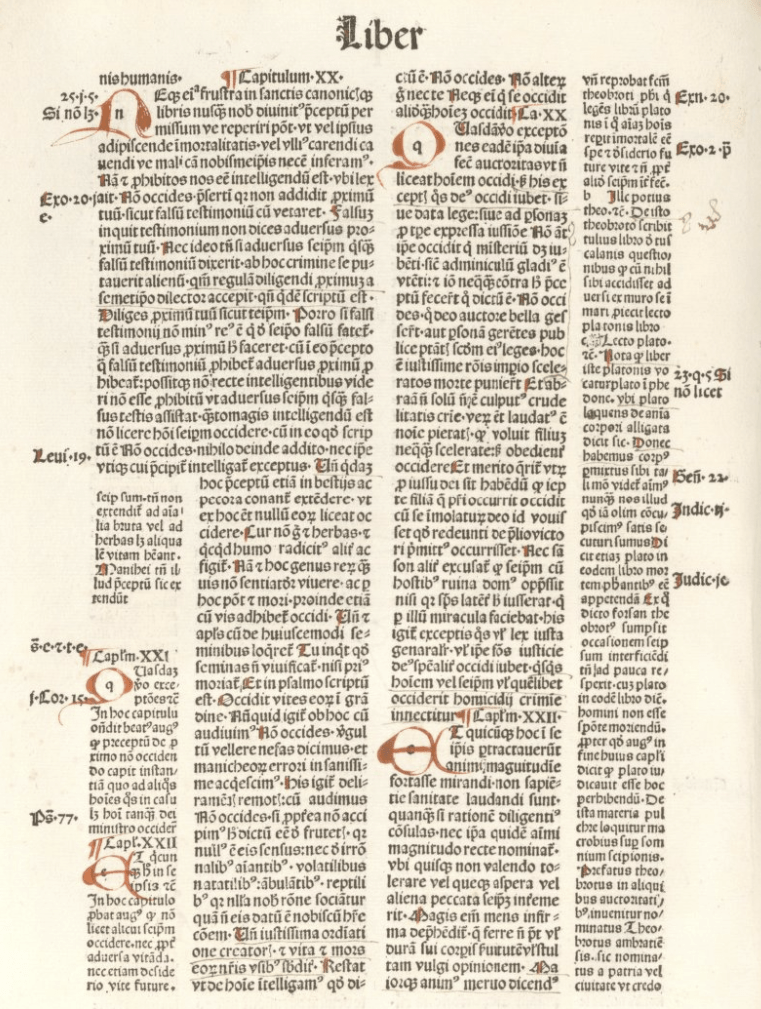

The edition of De civitate Dei, preserved in the Baltic Department of the Academic Library of Tallinn University, was printed in 1494 in Freiburg in Breisgau by Kilianus Piscator (Fischer) with commentaries by Thomas Valois (in English Thomas Waleys) and Nicolaus Triveth (in English Nicolas Trivet or Trevet). Thomas Waleys (ca. 1287 – after February 1349) was an English theologian, a Dominican monk, who taught at Oxford and in 1326–1327 at the University of Bologna. It was here that he wrote his commentary on Augustine’s work. Due to his disagreements with the doctrine of Pope John XXII, he was arrested by the Inquisition and held without trial for 11 years. After his release, he returned to England, where he probably died as an old man (more about him here). Nicolas Trivet (ca. 1258 – ca. 1328) was also a Dominican monk, best known as an Anglo-Saxon chronicler, whose works have inspired Chaucer, among others. Trivet, from Somerset, England, taught at Oxford University like Waleys and he also seems to have visited Italy (Florence). (see more)

Manuscripts of De civitate Dei were widespread in the Middle Ages. The work was first printed in Subiaco, Italy, in 1467, in an edition by German printers Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz. By the end of the 15th century, the work was already being printed in large numbers, the edition by Kilian Piscator being one of them. (see more)

The Tallinn copy has belonged to the Niguliste Church, the library of the Oleviste Church and from there to the collection of the Estonian General Public Library. Since both commentators on Augustine’s work were Dominican monks, it could be assumed that the print also reached Estonia through the Dominicans. The copy is not quite complete, page Q1 is missing. The print is decorated with blue and red hand-painted initials. The text is hand-rubricated in red. In addition to the comments, the work is also equipped with an index.

You can view this incunabulum in ETERA.